Scots History to 1400

By Michael Lynch

This is a section from the book "Scotland: a New History" by Michael Lynch which covers Scottish history from the earliest times to the present. There is an Index page of all the sections of the book up to the end of the 14th century which have been added to Rampant Scotland. The pages were previously part of the "Scottish Radiance" Web site.

The Making of the Kingdom of Fortriu

The history of the Picts can be likened to a mystery story with a few clues and no satisfactory ending. There is no firm explanation either of their origins before the third century AD or their disappearance in the mid-ninth century. Yet that period of over five centuries, too easily cast off as part of the 'Dark Ages', is crucial to any understanding of the mature medieval Scottish kingdom which would evolve after it. The period has, with justice, been called 'an age of migrations' when the different tribal peoples - Picts, Scots, Angles, Britons and Scandinavians - who inhabited the mainland of modern-day Scotland moved, fought, displaced and intermarried with each other. Yet the effort to plot these movements, either on a map or in the mind, is liable to produce too sharply etched a picture of coup and counter-coup, forced marches and counter-marches, and pitched battles with decisive results.

Whatever the Picts were, they are likely, as were other peoples either in post - Roman western Europe or in contemporary Ireland, to have been an amalgam of tribes, headed by a warrior aristocracy which was by nature mobile. Their culture was the culture of that warrior elite rather than of the people as a whole. Inevitably the historian's eye is attracted towards any core of 'facts', however suspect, to explain this mysterious people. Much of their history, as a result, has been written by deduction, either from the point where they first emerge in the annals of chroniclers, such as Bede writing of the sixth Century in his Ecclesiastical History compiled in the 720s, or where they disappear from history, in a conveniently neat palace coup conducted by the Dalriadic king, Kenneth mac Alpin in the 840s. But Bede was writing as the official spokesman of both the Northumbrian Church and royal house. His account was drawn up partly to justify the increasing influence of his own church in Pictland over the previous twenty years and perhaps also he was writing at the point where, with Pictish envoys coming to the Abbey of Jarrow to discuss Roman customs such as the dating of Easter, it was convenient for the reign of Nechtan, King of the Picts, to develop its origin legends. It found them not in the reign of Bridei, son of Maelchon and contemporary of Columba who died c.586, but twenty-eight kings and 943 years earlier in the legendary figure of Cruithne. For Bede himself, Ninian, operating from Whithorn sometime in the fifth century, was a more convenient apostle of the Picts than Columba, working from lona in the next century.

Alternatively, it is tempting to turn to the notion, which was much embellished from the late tenth century onwards, of a hostile take-over of the kingship by Kenneth mac Alpin in 840, followed a few years later by a wholesale and still more mysterious destruction of the Pictish nobility. What is undoubtedly mysterious is the extraordinary disappearance of the culture of the Pictish people within the course of the first two or three generations of mac Alpin kings. The intriguing history of a gens who dominated much of modern-day Scotland for five centuries or more should not he consumed by the story of an obscure intrigue that seemingly produced a genocide, of Pictish customs, law and culture.

The twentieth century has seen produced a number of versions of a case for the defence. Pictish art, Pictish studies and even Pictish politics are in vogue. The 1300th anniversary of the battle at Nechtansmere, celebrated in 1985 by a gathering at its site of Dunnichen Moss in Angus, saw it being hailed as the most decisive battle in Scottish history. Not the least of the many ironies of Scottish history may be that this most celebrated of all Pictish victories was won by a king of Picts whose father was a Dumbarton Briton; it has even been suggested that his opponent, Ecgfrith, King of Northumbria, was a rival external candidate. Defenders of the Picts have often conflicted on the detail, at times with that peculiar acrimoniousness which often marks out scholarly debate of the indeterminate. Most make common cause, however, in their stress on the distinctiveness of Pictish art, culture or customs.

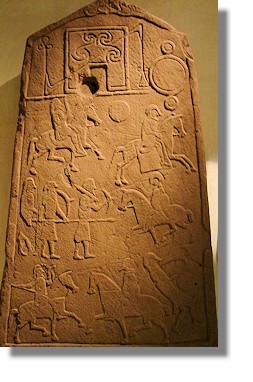

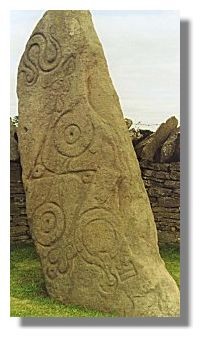

The best evidence is the standing stones of the Picts, which are sprinkled over the whole of the mainland of present-day Scotland from the Cromarty Firth to the Firth of Forth as well as in the Northern Isles and northern parts of the Western Isles. But how distinctive were these products of this enigmatic set of peoples?. The inspiration of these Pictish artists is deeply controversial: similarities between Pictish animal art and animal evangelist symbols in products of Celtic art such as the Book of Durrow have brought argument and counter-argument as to which was the inspiration of the other. The directions in which cultural influence flowed is debatable; the broad common heritage of Irish, Northumbrian and Pictish art, whether pre-Christian or Christian, can more readily be agreed. Pictland was not a self-contained enclave. There must have been regular links, flowing in both directions, between Pictland, Ireland and Northumbria. In each case, it may be permissible to think of a common culture stretching across the Irish Sea as well as north and south of Forth, even if each area had its own highly distinctive variants.

The haunting images of Pictish art and the intricate details of matrilinear succession, again often argued to be unique in the whole of Europe, have often been devised as answers to a very difficult historical problem - as a unique Pictish solution to the 'problem of the Picts'. Archaeologists in turn debate the aptness of terminology: whether 'Pictish' is appropriate to certain cultural patterns regardless of date or only to a specific historical period, between AD 300 and 850. The underlying uncertainty in this debate can be detected by the currency of a relatively new phrase 'proto-Pictish'. The overall effect has been an odd one: the Picts have become a curiosity rather than a major force in the telling of Scottish history. Their distinctiveness, argued so formidably by Pictish historians, has become the explanation for their disappearance from history. The case mounted on behalf of the Pictish 'world we have lost' has had a peculiar effect: as much as the efforts of those historians of medieval kingship looking for its roots and finding them in the mac Alpin dynasty, it has served to lose or obscure the real history of the Picts and their kings.

Scottish history before 1000, as a result, has come to be focused in the work of some recent historians on the question of the 'making of the kingdom', the complex process by which a cluster of different peoples - Britons and even some Scandinavians as well as Picts and Scots - came in the ninth and tenth centuries to owe common allegiance to a single king, 'of Scots'. The question is a legitimate one to ask of a process which was all the more noteworthy because both Ireland and southern England in the ninth century were still made up of a patchwork of fragmented and warring kingdoms. But the same question, in the case of Scotland, may also usefully be asked of the 'Dark Age' which came before the making of a mac Alpin dynasty of kings, for many of the forces which are often thought to have produced this new dynasty in the ninth century had been at work for three centuries or more. Before beginning to think of Scottish history as a series of watersheds, with the making of the mac Alpin kingdom in and after the 840s as one of the most vital, it may be as well to consider an alternative - of the making of a Pictish kingdom before it.

Origins of the Picts

The first mention of the Picts was made by a Roman observer in AD 297. The name itself, even if it simply meant 'painted people', was less a nickname than a nom de guerre, like that given by the Romans to the 'Franks', inhabitants of northern Gaul. Its occurrence at that point, when the main periods of both Roman invasion and occupation of a southern pale were already over, may suggest that the name implied a new power grouping in the north rather than indicating a tribe newly arrived from elsewhere. A hundred years before the name Picti appeared, the eleven or twelve northern tribes which Ptolemy had earlier described were already being subsumed into two great peoples, the Caledonii and the Maeatae, bound together in an alliance against the Romans. The Maeatae, explained Dio Cassius, c.310, 'live clse to the wall that divides the island into two parts' but the Caledonii are 'beyond them'. His dividing line between Roman and hostile territory would have been the Antonine Wall and the likely border between these two cognate peoples was the natural barrier of the Mounth. From this point until the sixth century, it is noticeable that there are consistently said to be two main groups of peoples north of the Forth/Clyde line: in 310 there is a reference to the 'Caledones and other Picts'; by 368 Ammianus Marcellinus describes the Dicalydones (obviously related to the Caledones) and the Verturiones; and Bede, in dealing with the sixth century, distinguishes clearly between 'northern Picts', a pagan people first touched by Columba in his mission up the Great Glen, and the 'southern Picts' who, he asserted, had been converted to Christianity much earlier by Ninian.

It is at this point that interpretation either becomes simpler or collapses into complex confusion under the weight of competing and changing tribal names. For Caledonii had also been one of the names of the dozen tribes described by Ptolemy in the second century AD. And what is to be made of the survey, the De Situ Albanie, which dates probably from the twelfth century, and some Pictish king lists which describe seven provinces of Pictland: four south of the Mounth and three to the north of it? Attached, as ever in the history of the Picts, is a legend, of the seven sons of Cruithne who each ruled a province, and each in his turn was overlord of an under-king. The divisions are more significant than the legend, which can be safely ascribed to the ingenuity of anonymous genealogists. South of the Mounth were the 'provinces' of Circenn (Angus and the Mearns), Fotla (Atholl), Fortriu (Strathearn and Menteith) and Fib (Fife). To the north were areas which are more difficult to draw with any precison. Ce covered Mar and Buchan, Fidach can be equated with Moray and Ross, but Cait probably extended beyond modem Caithness into southeast Sutherland.

These sources are impressionistic surveys made at a later date, with the advantage of hindsight. It is highly unlikely that these provinces all materialised at the same time, as part of a federal kingdom. There are significant gaps between the first mention of these provinces: Circenn appeared before 600 and Fortriu in 664, and these names may conceal much older divisions, perhaps even older than the Pictish kingdom itself. Fortriu was a later form of Verturiones. By contrast, neighbouring Fotla, which is first mentioned only in 739 as Athfotla ('new Ireland'), does suggest a newly recognised migrant tribe acquiring a territory. If there was a consolidation of a Pictish kingdom between the sixth and ninth centuries, it is unlikey to have taken the form of the amalgamation of neat territorial divisions, with a clear relationship between king and peoples.

Return to Index of Scots History to 1400