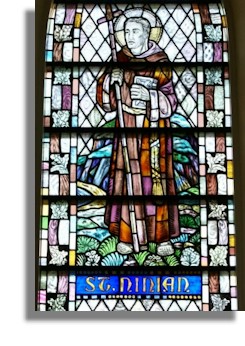

Hardest of all to determine is where the story should begin, for, like St Patrick, neither Ninian nor Columba can properly be thought of as a missionary in the modern sense of the term: all three almost certainly went to places where Christianity in some form already existed. Patrick and Ninian were not pioneers but bishops and it would have been unusual for a bishop even in the fifth century to be sent to work and die in a place beyond the known frontier if a community of Christians did not already exist there. Columba came, a century or so later in 563, not as a missionary but as a pilgrim; the role he cast for himself was that of the archetypal Irish pilgrim, the ascetic penitent. Ninian and Patrick were both Britons. Patrick, it has been argued, was born c.410, probably near Carlisle where he was educated, rather than as some have suggested further north in Strathclyde, and returned there about 445 before being sent as a bishop to Ireland c.460. (Graphic of stained glass window showing St Niniaan on the right is from Whithorn Priory)

The dates and nature of Ninian's career are much more a matter of speculation. Modern reviews of early saints conventionally ask for a date of birth: here is a saint for whom it would be difficult even to give the right century with any confidence. Bede does not say that Ninian was the founder or first bishop of St Martin's Church at Whithorn, the celebrated Candida Casa ('white house'). The graphic on the left is St Ninian's chapel at Whithorn (via Wikimedia). And the only clue to his precise period of operation is in an eighth-century work, the Miracula Nyniae Episcopi, which mentions a contemporary minor king called Tudwal. That king has been variously identified with both Man and the Dumbarton Britons, but even estimates of the period of the Strathclyde king vary from 450 to 570. If, as seems more likely, Ninian belongs to the same century as Patrick, it is possible that the origin of this already established Christian colony in Galloway may point to a direct sea link with Gaul, where Ninian had trained, as well as to the more obvious encroachment across the Roman frontier of Hadrian's Wall of Romano-British Christianity. By 500 the seat of the diocese seems to have shifted to Kirkmadrine, in the Rhinns of Galloway some twenty-five miles to the west, where inscribed stones commemorate two 'holy and outstanding bishops', Viventius and Mavorius.

The purpose of this see is obscure: Ninian's mission, according to Bede (pictured on the right, via Wikimedia), was to the southern Picts, but Kirkmadrine was so far west as to look more like a mission to the Irish. The shift of location and perhaps of focus is an odd commentary on Ninian's mission. Where did he make contact with the southern Picts? Some historians have seen him as far north as Fife or even Angus, both across the formidable barrier of the 'sea of Scotland'. Others have speculated that Pictish occupation south of the natural frontier of the Forth/Clyde line in the fifth century is a more plausible explanation than long-distance expeditions by Ninian to the north of it. The most likely area where contact was made, apart perhaps from possible scattered Pictish enclaves further east in Lothian, was in the frontier triangle bounded by present-day Edinburgh, Stirling and Glasgow, which would for long mark the uncertain and shifting boundaries between the kingdoms of the Picts, Strathclyde Britons and Bernicia. This was the frontier land competed for by Picts and Britons in the fifth and sixth centuries and which the Angles would win and lose in the course of the seventh. Saints, Ninian included, were to kings weapons of war rather than bringers of peace. Here too are significant numbers of Eccies- place names suggesting early churches and dedications. It would not be surprising if, for one reason or another, already by 540 a legend had grown up of Ninian consecrating a cemetery at St Ninians near Stirling, the linchpin of the three frontiers.

The purpose of this see is obscure: Ninian's mission, according to Bede (pictured on the right, via Wikimedia), was to the southern Picts, but Kirkmadrine was so far west as to look more like a mission to the Irish. The shift of location and perhaps of focus is an odd commentary on Ninian's mission. Where did he make contact with the southern Picts? Some historians have seen him as far north as Fife or even Angus, both across the formidable barrier of the 'sea of Scotland'. Others have speculated that Pictish occupation south of the natural frontier of the Forth/Clyde line in the fifth century is a more plausible explanation than long-distance expeditions by Ninian to the north of it. The most likely area where contact was made, apart perhaps from possible scattered Pictish enclaves further east in Lothian, was in the frontier triangle bounded by present-day Edinburgh, Stirling and Glasgow, which would for long mark the uncertain and shifting boundaries between the kingdoms of the Picts, Strathclyde Britons and Bernicia. This was the frontier land competed for by Picts and Britons in the fifth and sixth centuries and which the Angles would win and lose in the course of the seventh. Saints, Ninian included, were to kings weapons of war rather than bringers of peace. Here too are significant numbers of Eccies- place names suggesting early churches and dedications. It would not be surprising if, for one reason or another, already by 540 a legend had grown up of Ninian consecrating a cemetery at St Ninians near Stirling, the linchpin of the three frontiers.

But what of the evidence of a mission by Ninian further north, beyond the Forth and even beyond the Tay into Angus? The specific evidence of dedications to Ninian and the general pattern of finds of long cist cemeteries to the north of the Forth both argue for his influence there, and especially in Fife, but there was also a vogue in the twelfth century of dedications to Ninian which can lay false trails. With Ninian, perhaps more than with any other of Scotland's saints, the work of the man and the work of the cult are difficult to separate. The inhabitants of east Fife were, at least according to Bede, still pagan when Cuthbert, an Anglican monk from Melrose, was driven ashore in a storm in the mid-seventh century. If Christianity spread north from Whithorn through the river valleys of the Nith and. Clyde, as well as consolidating in the easier terrain of the Tweed basin to the east, it must have taken the work of successive generations of Ninian's missionaries as well as his own lifetime. As in Ireland, the mission probably moved at the pace of the conversion of ruling families. By c.600 it had spread eighty miles to the north, allowing Kentigern to be established as the first bishop of the Dumbarton kingdom of Strathclyde; his seat, probably at Govan rather than Glasgow, marked the northern most extent of the Ninianic mission some 150 years after his death. (The graphic on the left is of a "chape" from sword scabbard, probably made in Mercia in the late 8th century, part of the St Ninian's Isle Treasure which was discovered under a cross-marked slab in the floor of the early St. Ninian's church in Shetland in 1958 by a local schoolboy. Graphic via Wikimedia).

But what of the evidence of a mission by Ninian further north, beyond the Forth and even beyond the Tay into Angus? The specific evidence of dedications to Ninian and the general pattern of finds of long cist cemeteries to the north of the Forth both argue for his influence there, and especially in Fife, but there was also a vogue in the twelfth century of dedications to Ninian which can lay false trails. With Ninian, perhaps more than with any other of Scotland's saints, the work of the man and the work of the cult are difficult to separate. The inhabitants of east Fife were, at least according to Bede, still pagan when Cuthbert, an Anglican monk from Melrose, was driven ashore in a storm in the mid-seventh century. If Christianity spread north from Whithorn through the river valleys of the Nith and. Clyde, as well as consolidating in the easier terrain of the Tweed basin to the east, it must have taken the work of successive generations of Ninian's missionaries as well as his own lifetime. As in Ireland, the mission probably moved at the pace of the conversion of ruling families. By c.600 it had spread eighty miles to the north, allowing Kentigern to be established as the first bishop of the Dumbarton kingdom of Strathclyde; his seat, probably at Govan rather than Glasgow, marked the northern most extent of the Ninianic mission some 150 years after his death. (The graphic on the left is of a "chape" from sword scabbard, probably made in Mercia in the late 8th century, part of the St Ninian's Isle Treasure which was discovered under a cross-marked slab in the floor of the early St. Ninian's church in Shetland in 1958 by a local schoolboy. Graphic via Wikimedia).

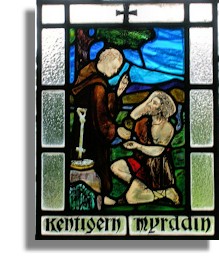

Kentigern may himself give the lie to overrigid notions of the missionary frontier; he may have been born in what was the territory of the Gododdin, perhaps near Culross on the northern shore of the Forth. (The graphic of stained glass in Stobo Kirk, via Wikimedia, is of St Kentigern converting Myrddin) If so, he crossed the frontier to pursue his career as a holy man. But little of this is apparent in 'official' accounts of him. The firmest fact known about this celebrated but enigmatic figure; the rogue amongst the communion of Scottish saints, is the date of his death, c.612. Some historians have even speculated that he is a composite figure, groomed if not born in the imagination of his hagiographers. Most that is known comes from a twelfth century Life of Kentigern written by Jocelyn, a monk of Fumess. Some have thought that this drew on an older Life, though estimates of how old that was range from the early seventh century to c. 1000. Whatever its age, its results can be seen reproduced in Jocelyn's later Life, an unlikely picture of a Briton transformed into a saint of the Celtic Church, whose holiness is attested by a string of miracles, all the asceticism and more of a Colum Cille, and encounters with other Celtic saints. Like kings, religious centres as they gathered in prestige needed a foundation legend and it may be that the first attempt to provide one came within a century or so of Kentigern's death. If this is so, it is intriguing that Glasgow, so close to the seat of the kings of Strathclyde, by C. 700 may have wanted a Gaelic saint rather than a British one.

Kentigern may himself give the lie to overrigid notions of the missionary frontier; he may have been born in what was the territory of the Gododdin, perhaps near Culross on the northern shore of the Forth. (The graphic of stained glass in Stobo Kirk, via Wikimedia, is of St Kentigern converting Myrddin) If so, he crossed the frontier to pursue his career as a holy man. But little of this is apparent in 'official' accounts of him. The firmest fact known about this celebrated but enigmatic figure; the rogue amongst the communion of Scottish saints, is the date of his death, c.612. Some historians have even speculated that he is a composite figure, groomed if not born in the imagination of his hagiographers. Most that is known comes from a twelfth century Life of Kentigern written by Jocelyn, a monk of Fumess. Some have thought that this drew on an older Life, though estimates of how old that was range from the early seventh century to c. 1000. Whatever its age, its results can be seen reproduced in Jocelyn's later Life, an unlikely picture of a Briton transformed into a saint of the Celtic Church, whose holiness is attested by a string of miracles, all the asceticism and more of a Colum Cille, and encounters with other Celtic saints. Like kings, religious centres as they gathered in prestige needed a foundation legend and it may be that the first attempt to provide one came within a century or so of Kentigern's death. If this is so, it is intriguing that Glasgow, so close to the seat of the kings of Strathclyde, by C. 700 may have wanted a Gaelic saint rather than a British one.

The purpose of this see is obscure: Ninian's mission, according to Bede (pictured on the right, via Wikimedia), was to the southern Picts, but Kirkmadrine was so far west as to look more like a mission to the Irish. The shift of location and perhaps of focus is an odd commentary on Ninian's mission. Where did he make contact with the southern Picts? Some historians have seen him as far north as Fife or even Angus, both across the formidable barrier of the 'sea of Scotland'. Others have speculated that Pictish occupation south of the natural frontier of the Forth/Clyde line in the fifth century is a more plausible explanation than long-distance expeditions by Ninian to the north of it. The most likely area where contact was made, apart perhaps from possible scattered Pictish enclaves further east in Lothian, was in the frontier triangle bounded by present-day Edinburgh, Stirling and Glasgow, which would for long mark the uncertain and shifting boundaries between the kingdoms of the Picts, Strathclyde Britons and Bernicia. This was the frontier land competed for by Picts and Britons in the fifth and sixth centuries and which the Angles would win and lose in the course of the seventh. Saints, Ninian included, were to kings weapons of war rather than bringers of peace. Here too are significant numbers of Eccies- place names suggesting early churches and dedications. It would not be surprising if, for one reason or another, already by 540 a legend had grown up of Ninian consecrating a cemetery at St Ninians near Stirling, the linchpin of the three frontiers.

But what of the evidence of a mission by Ninian further north, beyond the Forth and even beyond the Tay into Angus? The specific evidence of dedications to Ninian and the general pattern of finds of long cist cemeteries to the north of the Forth both argue for his influence there, and especially in Fife, but there was also a vogue in the twelfth century of dedications to Ninian which can lay false trails. With Ninian, perhaps more than with any other of Scotland's saints, the work of the man and the work of the cult are difficult to separate. The inhabitants of east Fife were, at least according to Bede, still pagan when Cuthbert, an Anglican monk from Melrose, was driven ashore in a storm in the mid-seventh century. If Christianity spread north from Whithorn through the river valleys of the Nith and. Clyde, as well as consolidating in the easier terrain of the Tweed basin to the east, it must have taken the work of successive generations of Ninian's missionaries as well as his own lifetime. As in Ireland, the mission probably moved at the pace of the conversion of ruling families. By c.600 it had spread eighty miles to the north, allowing Kentigern to be established as the first bishop of the Dumbarton kingdom of Strathclyde; his seat, probably at Govan rather than Glasgow, marked the northern most extent of the Ninianic mission some 150 years after his death. (The graphic on the left is of a "chape" from sword scabbard, probably made in Mercia in the late 8th century, part of the St Ninian's Isle Treasure which was discovered under a cross-marked slab in the floor of the early St. Ninian's church in Shetland in 1958 by a local schoolboy. Graphic via Wikimedia).

Kentigern may himself give the lie to overrigid notions of the missionary frontier; he may have been born in what was the territory of the Gododdin, perhaps near Culross on the northern shore of the Forth. (The graphic of stained glass in Stobo Kirk, via Wikimedia, is of St Kentigern converting Myrddin) If so, he crossed the frontier to pursue his career as a holy man. But little of this is apparent in 'official' accounts of him. The firmest fact known about this celebrated but enigmatic figure; the rogue amongst the communion of Scottish saints, is the date of his death, c.612. Some historians have even speculated that he is a composite figure, groomed if not born in the imagination of his hagiographers. Most that is known comes from a twelfth century Life of Kentigern written by Jocelyn, a monk of Fumess. Some have thought that this drew on an older Life, though estimates of how old that was range from the early seventh century to c. 1000. Whatever its age, its results can be seen reproduced in Jocelyn's later Life, an unlikely picture of a Briton transformed into a saint of the Celtic Church, whose holiness is attested by a string of miracles, all the asceticism and more of a Colum Cille, and encounters with other Celtic saints. Like kings, religious centres as they gathered in prestige needed a foundation legend and it may be that the first attempt to provide one came within a century or so of Kentigern's death. If this is so, it is intriguing that Glasgow, so close to the seat of the kings of Strathclyde, by C. 700 may have wanted a Gaelic saint rather than a British one.