Scots History to 1400

By Michael Lynch

This is a section from the book "Scotland: a New History" by Michael Lynch which covers Scottish history from the earliest times to the present. There is an Index page of all the sections of the book up to the end of the 14th century which have been added to Rampant Scotland. The pages were previously part of the "Scottish Radiance" Web site.

Columba and Iona

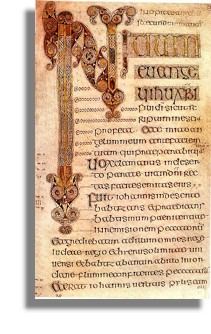

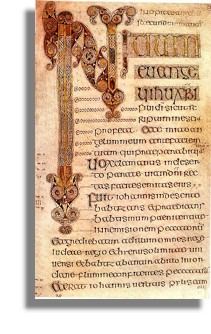

The natural axis of the Ionan Church in Columba's lifetime was the Irish Sea. The Amra already acclaimed him as the 'protector of a hundred churches'. Where they were is difficult to say, at least in Ireland: many church dedications to him are to be found in the lands of the northern Uí Néill but none is explicitly mentioned in the annals before the seventh century. The important foundation of the monastery of Durrow in the southern Uí Néill lands may, however, have taken place in the last years of his life. The graphic on the right is of the Book of Durrow illuminated manuscript 9from Wikimedia). In Dalriada, Columba must have overseen the foundations on the mysterious islands of Hinba and Elen, at Cell Diuni to the south on the shores of Loch Awe, and at Campus Lunge, somewhere on Tiree to the north, as well as considerable activity on Skye. These were the beginnings of the Columban paruchia, a vast family chain of monasteries which within little more than a century of his death would stretch from the shores of the Moray Firth to the north of Ire land and as far south as Kells, founded in 807. Yet if only the skeleton of this paruchia was in place before 600, there can be no doubt that Columba was acknowledged within his own lifetime as both the vital head of this monastic family and as the confidante and protector of kings on both sides of the Irish Sea. A year after his ordination of Aedán as King of Dalriada, Columba was at the Convention of Druim Cett in 575 establishing an alliance of kings across the water and fostering a future high king of the Uí Néill. The key to the advancement of the Columban paruchia was the patronage of kings, both in Ireland and Dalriada.

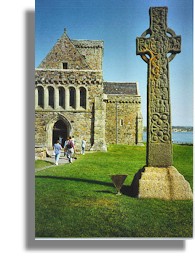

Iona was the vital umbilical cord which linked the different parts of this monastic empire (graphic on the left of Iona Abbey from the sea is by Phillup Capper, via Wikimedia). Small though the island was, it acted as a base camp housing what were probably sizeable numbers of monks. There they lived in individual cells made of turf or stone. One historian has speculated that the ten-acre site of the vallum would have accommodated at least twenty monks, but it is known that sixty-eight were massacred on the island in a Viking raid of 806. Both the early Amra and the later Life written by Adomnán suggest a community of 150 or more. Not all these were monks: the community was naturally divided into teachers, student deacons, workers and the active ministry. Most almost certainty came from Ireland, which was both Iona's strength and its eventual weakness. The great plague in Ireland of 664 probably did more than the Synod of Whitby in the same year to weaken its mission. When the Viking raids began - and Iona was attacked three times between 795 and 806 - the natural instinct of most of the community was to withdraw to the safety of Ireland, and especially to the new foundation at Kells. To some Irish historians, this has signalled the beginning of the displacement of Iona by Kells as the natural centre of the Columban world, but the seniority of Dunkeld suggests that it was Iona's main heir.

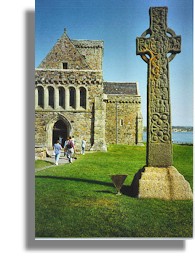

Columba was an abbot and a pilgrim. Iona fitted both roles to perfection. (Graphic here is of Iona Abbey and St Martin's Cross by Tom Richardson, via Wikimedia) This busy transit camp of the Columban paruchia became in Adomnán's Life, written c.690 at what must have been the peak of its activity, a 'small and remote island of the Britannic ocean'; Iona was recast as the backdrop for his picture of a simple holy man, giving it a timelessness and universality which rings deep chords even to this day. Prophet, apostle and pilgrim - his vision of Columba is a compelling one, which was designed to elevate its subject amongst the saints not just of the Irish Church but of western Christendom as a whole.

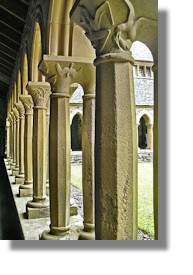

Adomnán's Life was in itself an exercise in piety, but it was also a skillfully disguised political tract for its times. It was written only twenty-five years after the Synod of Whitby, where not only the leadership of Iona had been challenged by one of its own converts, the infant Church of Northumbria which had begun on Lindisfarne in the 630s under the guidance of Aidan, but the very reputation of Columba had been called into question. (Graphic on the left is of the present-day cloisters at Iona Abbey)The issues of the dating of Easter and the tonsure camouflaged what was in essence a dispute over jurisdiction, one made more complicated by the secular politics of the court of Oswiu, King of Northumbria. This was not simply a clash between a Celtic and a Roman Church. In the course of the seventh century these issues would create tensions in the Churches of England, Pictland and Ireland. Iona was out of step with most of the Irish Church which had accepted these changes in 630. Like the Irish Church, that in Northumbria was of at least two minds: the dispute at Whitby in 664 was the first instalment of what by the 670s would crystallise as a struggle within it between Lindisfarne and Ripon, whose newly dedicated church and building programme marked the favour shown to it by the AngIian court. By invoking the authority of St Peter as superior, Wilfrid, a monk of Lindisfarne but also future bishop at Ripon and the spokesman for the Roman party in the Northumbrian Church, in 664 had called in question the cult of Columba.

The tract of the Ionan abbots, Ségéne and his nephew Cumméne, was the first blast of the trumpet against Wilfrid; Adomnán's Life was the second, more subtly tuned one. At once selective with the facts and concerned only with the essential truth of Colum Cille, it took its subject out of the sphere of ecclesiastical politics into which he had been dragged by Wilfrid in 664. The most notable achievement of the expanding Columban Church - the founding of Lindisfarne in 635 - went unmentioned; little or nothing was said of the power and prestige of the Ionan paruchia. This was the life of a simple man of God whose simplicity mattered above all else. It has been the picture of Columba which has predominated ever since.