Scots History to 1400

By Michael Lynch

This is a section from the book "Scotland: a New History" by Michael Lynch which covers Scottish history from the earliest times to the present. There is an Index page of all the sections of the book up to the end of the 14th century which have been added to Rampant Scotland. The pages were previously part of the "Scottish Radiance" Web site.

Saintly Rivalries

This compelling vision of Colum Cille was made at the expense of other members of the Columban Church, both in his lifetime and after, and also of missionaries who did not belong to the Ionan paruchia. There are many heroes of the Celtic Church as a whole whose efforts have remained largely unsung. Two other Irish monks, Comgall of Bangor and Brendán of Clonfert (stained glass window of St Brendan on the right was photographed by Andreas F Borchert, via Wikimedia), who both visited Columba on Iona, probably founded monasteries on Tiree, only twenty miles to the north-west of Iona and an alternative natural staging post for a monastic-based mission.

Brendán, better known as the navigator of the North Atlantic, may also have founded a monastery on the Garvellach Islands in the Firth of Lorne, now remote but then another potential offshore base for a mission to the territory of the Cenél Loairn. Another monk of Bangor and contemporary, Moluag, made as his base the much larger island of Lismore further up the same Firth of Lorne (The graphics of the Celtic cross on the shore of Lismore on the left and the graphic of Lismore island below are both via Wikimedia). It was best located of all for a mission to the Cenél Loairn, a fact reflected in its choice as the seat of bishops of Argyll in the twelfth century.

The most explicit rivalry in the late sixth century lay between Columba's Iona and Donnán, who was based on the island of Eigg, between Iona and Skye and adjacent to the territory of northern frontier between the Cenél Gabráin and which had a community of no less than 150 in 617, became the focal point of a rival Celtic paruchia spreading over much of north-western Pictland the Picts. Eigg (graphic of Eigg on the right is by L J Cunningham, via Wikimedia). Dedications to Donnán range from Caithness and eastern Sutherland on the far north-eastern mainland to the Outer Isles of South Uist and Lewis in the far west; from Kildonan or Cille Donnain on the mainland in the north of Western Ross beside Little Loch Broom to the islands of Kishorn and Eilean Donan, strategically placed in Loch Carron and Loch Aish on the northern approaches to Skye from the mainland.

The frontier between the churches of Columba and Donnán lay on Skye itself, where there may have been outright competition. Columba died the death of a white martyr, collapsing 'weary with age' before the altar of his church on Iona; Donnán and his community on Eigg died as red martyrs, massacred reputedly after a celebration of the mass in 617. (Graphic of the ruined chapel of Kildonnan is by Michael Wills, via Wikimedia) The community on Eigg was revived early in the eighth century, for a list of holy men associated with it survives in the Annals of Ulster, but their names are their only witness. It almost certainly had disappeared before the end of that century when confronted by a renewed threat of violence, this rime from the Vikings. The inheritor of Donnán 's mission to the north-west was probably another monk from Bangor, Máelrubai, rather than a revived community on Eigg. The impact of Máelrubai's foundation in 673 at Applecross, on the mainland of Western Ross directly looking over to the heart of Skye, extended across the north-west from Skye to Dingwall in the footsteps of Donnán and perhaps beyond.

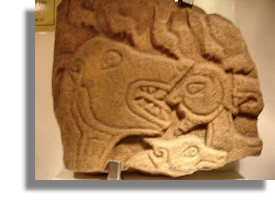

Although Columba, as has been seen, was the inspirer of a mission rather than a missionary himself, it may be that his expedition to the court of the northern Pictish king, Bridei, was in part to secure permission for a north-eastern mission to the Picts. If that is so, it is unlikely that much came of this mission before c.650. Geography and a rash of Christian standing stones, of both Class II and III, may combine to suggest that Rosemarkie, a natural terminus at the end of the Great Glen situated on the Black Isle on the northern shore of the Moray Firth, may have been a forward base for this post-Columban mission. (Apart from the main "Rosemarkie Stone" in Rosemarkie, on the Black Isle of Easter Ross, the most widely known is the so-called "Daniel Stone" (see graphic on the right, via Wikimedia). The stone is so named because of the tendency among scholars and enthusiasts of Pictish art to give every Pictish stone a Christian interpretation. In this case, the depiction of a man's head at the jaws of a wolf-like beast is supposed to depict the Old Testament story of Daniel in the Lion's Den).. Rosemarkie is associated with the shadowy figure of its bishop, Curetán, who would later be reclaimed by the Roman party in the Pictish church as St Boniface.

The spread of Ionan influence further east, into Aberdeenshire, is more enigmatic still. The work of the real foot soldiers of the post-Columban Church remains an unwritten chapter in its history; it may be glimpsed, occasionally, in dedications to what seem to be strictly local saints, such as St Ternan or St Machar near Aberdeen (See graphic on the left of St Machar Cathedral, Aberdeen, via Wikimedia) who do not figure in the Martyrology of Óengus, the 'who's who' of saints of the Irish Church. And the frontier between the Ionan mission, which by the last quarter of the seventh century must have received some official recognition by both the Pictish Church and Pictish kings, and a rival mission pushing northwards from Fortriu is uncharted territory. By then, however, the most important figure in the mission was Adomnán himself, who was probably a regular visitor to Pictland.

Return to Index of Scots History to 1400