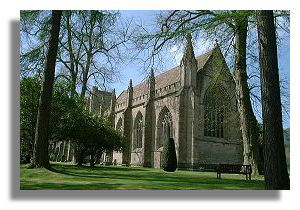

The first duties of holy men were as the magicians and clerks of kings rather than acting as their conscience. Magic was demonstrated at the inauguration of a king or at his victory in battle; Aedán mac Gabráin prospered after he was ordained by Columba as King of Dalriada in 574 but his grandson Domnall Brecc met with a series of catastrophes ending in his death in 642 because, it was said, he had breached the promise made by his own kindred to remain faithful to Iona and the Irish family of Cenél Conaill. It is no coincidence that the appearance of origins legends of a line of kings, as perhaps in the reign of Nechtan (706-24), coincided with the emergence of an active clergy around the king. The graphic here is of the ruins of Restenneth Priory which may even have been built on the site of a Pictish church dedicated to St Peter (mentioned in Bede) built in 710 for Nechtán mac Der Ilei, King of the Picts. Clerics brought to the person of kings a heightened sense of the old ways, as the bringer of benefits and victories, before they promulgated a new view of kingship. Yet that came too.

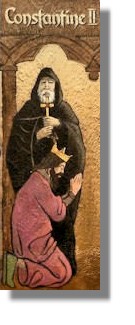

The literate clergy were a mandarin class which forged a role for itself as the advocates and interpreters of high kingship. Columba and Adomnán concerned themselves with overkings, of Dalriada and of Picts, who were worthy of Christian record, like kings of Judah and Israel. The merging of different peoples under an overking of Picts in the eighth and ninth centuries was accompanied by the cultivation of different traditions of saints as well as the compilation of genealogies of kings by the learned orders. In the course of the eighth century, the Church of the Picts in turn adopted a cult of Peter, probably in the reign of Nechtan, and a cult of Andrew, perhaps in the next important reign, of Óengus (729-61). Both of these long reigns and especially that of Constantine (789-820) saw, it is likely, a flowering of officially sponsored ecclesiastical art of various kinds. It is not surprising that Pictish kings should begin to see themselves as God-given patrons of the Church after the fashion of the Roman Christian Emperor Constantine. The adoption by Pictish kings of the cult of Constantine (King Constantine II who is shown on the left in typically pious mode was one of no less than four kings so called between 789 and 997) mirrors its growing popularity after c.750 in western Europe, where the majesty of kingship and its nearness to God became increasingly intertwined, especially with the reign of Charlemagne.

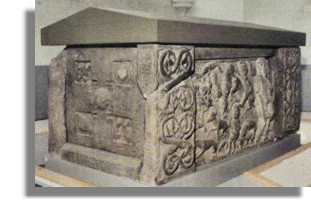

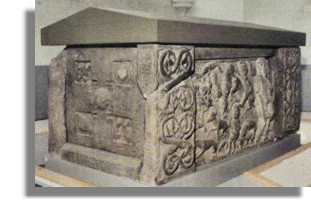

The most striking religious image sponsored by a Pictish king is the St Andrews tomb shrine (See graphic from Wikipedia on the right), which (in similar vein to that at Meigle showing Daniel in the lions' den) depicts David holding open the jaws of a lion. It has similarities, too, with motifs in the Book of Kells, which was begun probably on Iona in the late eighth century. The purpose of this stone-built shrine or sarcophagus, nearly six feet in length with elaborately carved panels and corner posts, which was found by workmen digging in the precincts of the later Cathedral in 1833, is unclear; perhaps it was to hold the relics of a saint, such as Andrew or Regulus, the legendary carrier of Andrew's bones to Scotland. There is also a crucial difference between it and the Brecbennach. Columba's shrine in this form was portable, designed to be carried throughout the Ionan paruchia. The bewildering journeys of Columba's relics back and forward across the Irish Sea from their base on Iona in the seventh and eighth centuries were part of a saint's progress among the faithful. The St Andrews sarcophagus, in contrast, suggests a Church based firmly in an established royal centre rather than a missionary one. It hints at a Church of kings of Picts and Scots rather than a pan-Celtic one.

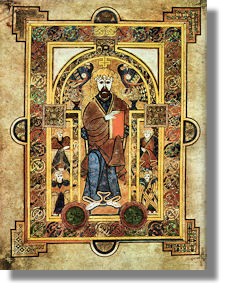

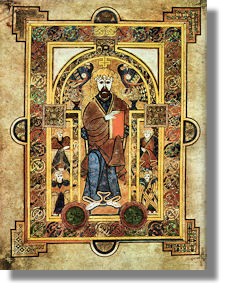

The cult of Columba was, however, still too powerful to be cast aside by these kings. Iona itself had been abandoned in 807 in the face of the Viking threat; most monks went probably to Ireland and only a token community was left behind. In the 840s the emblems of Columba were split, going west or east to the safer parts of the old Ionan paruchia. What is now known as the Book of Kells (picture here via Wikimedia) went from Iona to the new monastery at Kells; the fragmentary psalter known as the Battler also went to Ireland. The Brecbennach went east, as did Columba's crozier. His relics themselves were divided up in 849 to what in effect were now almost separate daughter churches, although Dunkeld could lay claim to seniority. In Ireland, the centre of Columba's paruchia shifted first to Kells and, in the mid-twelfth century, to Derry. in Scotland, the cult of Columba followed Kenneth mac Alpin eastwards to the royal and religious centre which he established at Dunkeld.

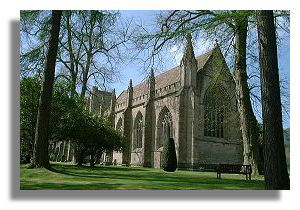

What Kenneth was doing was no more than a continuation of a process begun by previous kings of Picts. The two religious centres of the emerging kingdom of the Scots were at Dunkeld (modern cathedral in Dunkeld picured here) and St Andrews, carefully dedicated to different traditions of saints. It was a distinctively Scottish solution to a Scottish problem. In the ninth century Gaelic-named kings of Picts still chose to be buried in the sacred place of Iona. On the other hand, it had been a Pictish king with the very Gaelic name of Óengus who had founded a church at Kilrimont dedicated to a new, exotic saint, thereby creating a royal centre which would, as St Andrews, shortly become the focal point of the Church of the mac Alpin dynasty. The very nature of ninth- and-tenth century kingship was composite; so was its Church.